Given how tough it is to write “the perfect chapter one,” no wonder so many people talk about writing a novel, and never do it.

Given how tough it is to write “the perfect chapter one,” no wonder so many people talk about writing a novel, and never do it.

You may have seen articles championing the dos, don’ts, and cardinal sins of chapter one. But read a stack of best sellers, and you’ll find a slew of “sinners” who made tons of money.

Forget about perfection. There’s no chapter one that will please every agent, publisher, or reader. And when starting a Herculean project like writing a book, perfection is your enemy.

Think in terms of what you want to accomplish, not what you’re terrified of doing wrong, and you’ll end up with a solid draft of chapter one that you can keep improving.

Here’s a checklist to help you roll up your sleeves and draft the dreaded chapter one:

1.) Write a Killer First Sentence: Sentence one is like that opening shot in a great film. Purposeful “linguistic cinematography” is necessary to impress the audience.

Again, sentence one doesn’t have to be completely perfect at this stage, but even in draft form, this sentence should intrigue or inspire. Ideally sentence one resonates with something central to character, setting, or plot.

Check out this opening sentence from Max Brooks’s World War Z:

“The first outbreak I saw was in a remote village that officially had no name.”

On the surface, this sentence might not seem masterful or poetic like Dickens’ famous openers, but we’ve got a place and we’ve got a problem. There’s a sense of dread and impending doom. A feeling of isolation. A mystery brewing. That’s a sentence that launches a blockbuster zombie apocalypse!

Don’t overthink your first sentence. Just use that opportunity to tell the reader a concrete, meaningful idea about the person, place, or situation at hand. Your opening sentence should gel with the whole hook of where you start your story. It can be action, description, a simple fact, or even a line of dialogue; but it needs to really matter.

2.) Appeal Your Character: In spite of what some will say, it’s often okay if the POV or focal character of chapter one isn’t necessarily your main character. Just know why you’re starting with that character and give that character something to do that matters.

The title of Blake Snyder’s excellent screenwriting book Save the Cat refers to a moment early in the screenplay where the protagonist should do something the audience can respect. That thing doesn’t actually have to be saving a cat, but we need a reason to care about these people (good or bad).

I’ve published three novels and had a different approaches to the POV character in all three openings:

Make Us Love Your Hero: My horror adventure Violet Black and the Curse of Camp Coldwater opens with 13-year-old paranormal investigator Violet intervening when she sees a peer being bullied. The reader knows right away that we have a hero who goes out of her way to do the right thing.

It’s like when Steve Rogers stands up to that disrespectful movie-goer, before he gets his super solider serum, at the beginning of Captain America: The First Avenger. Steve is a good guy! He stands up for what’s right, even if he’s going to get beat up for it.

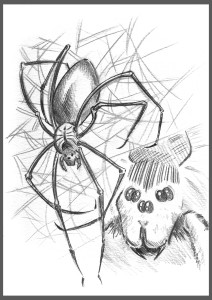

Make Us Respect a Supporting Character: In chapter one of my book Jimmy Chimaera & the Temple of Champions, we meet a heroic spider named, putting his life on  the line (literally) to complete his mission. Counselor Speck isn’t the central main character, but he will become Jimmy’s mentor, and the audience can respect his determination for being an underdog. A (literal) little guy in a big world of high stakes challenges. As a bonus, starting with a spider’s POV immediately informs the reader that they’re about to read a book with an extraordinary world of fantastic possibilities.

the line (literally) to complete his mission. Counselor Speck isn’t the central main character, but he will become Jimmy’s mentor, and the audience can respect his determination for being an underdog. A (literal) little guy in a big world of high stakes challenges. As a bonus, starting with a spider’s POV immediately informs the reader that they’re about to read a book with an extraordinary world of fantastic possibilities.

You may recall that the Harry Potter series doesn’t exactly open with the title character. It opens with Harry’s future mentors begrudgingly leaving him in the care of his rotten relatives—where he will be safe. You learn how important Harry is through how much these Hogwarts teachers care about him.

Make Us Hate Your Villain: Chapter one of my fantasy adventure Jake Carter & the Nightmare Gallery is told from the POV of a boy being pursued and punished by the  story’s villains. We get a sense of just how nasty the bad guy is, and what this could mean for the main character we’re about to meet in chapter 2.

story’s villains. We get a sense of just how nasty the bad guy is, and what this could mean for the main character we’re about to meet in chapter 2.

Remember the opening scene of Inglorious Basterds where Col. Hans “Jew Hunter” Landa (Christoph Waltz) chit-chats, enjoys a glass of milk, and prepares to exterminate the innocents under the floor boards? Pay attention to how many great movies open with the villain doing something evil. It works in books too!

Not every chapter one character needs to be heroic, or even the main character, but they should have appeal. Can you make us pity or fear an important character? Compassion and respect come in strange packages sometimes. Give the reader cause to invest.

3.) Lay Some Groundwork: Avoid an info dump, but allow important backstory to start trickling in.

Chapter one of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit is downright instructional, but in a charming, fun way. We learn a lot about what a Hobbit is and where they live. We learn a bit about wizards, dwarves, and the game of golf, but not everything. Middle Earth is a big place, and Tolkien probably didn’t even realize how big when he first wrote this chapter, but he gives a hearty dose of history and context, enough fuel to get us through the beginning of this journey.

4.) Set the Plot in Motion: It’s best to end every chapter with a hook that drives the reader into the next chapter, but it’s especially important to give the reader enough drama and conflict in chapter one to make them want to read the next twenty, forty, or fifty chapters. Make the stakes clear and compelling.

Even if the reader has yet to discover the major conflict of the whole story, there should be an immediate BIG problem, goal, or mystery the reader cannot turn away from. Ideally that situation will only get more sticky, convoluted, and complex with each chapter for many chapters to come; but for now, just set things in motion.

If the first domino hasn’t fallen by the end of chapter 1, you might need to start your novel with chapter 2 instead.

In his middle grade mythology-inspired series (Percy Jackson, Heroes of Olympus, et al.), Rick Riordan uses opening chapters to endear the reader to a charming, admirable teen protagonist. He then swiftly suggests a mystery about the hero’s origins. (Could this kid’s parent be an ancient deity?) And then by the end of the chapter, a vicious mythological beast shows up and threatens to kill the poor kid. Chapter two is guaranteed to be an epic battle between a teenage demi-god and a blood-thirsty monster. Who wouldn’t keep reading?

Of course every novel is unique. Your chapter one might break or bend some of those rules, just know why you have to do what you have to do, and don’t sweat perfection.

At least, not until you finish the epilogue and look back.

Connect with Kevin M. Folliard on . . .

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kevinfolliard

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Kmfollia